Aboriginal Rights and GEOGRAPHY

Land Rights:

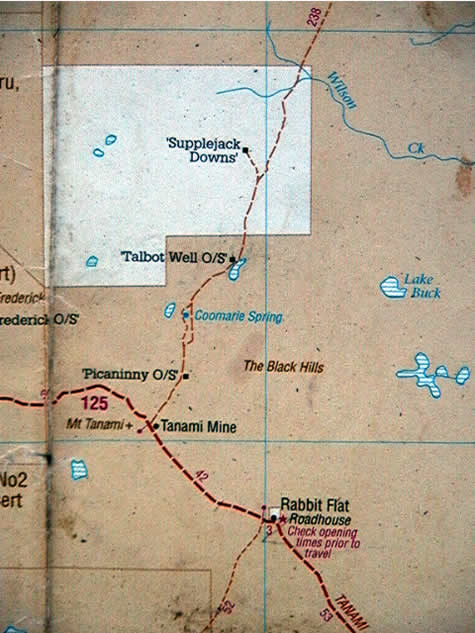

Since Alice Springs we’ve been biking through predominantly aboriginal freehold land. This means the land was given back to the traditional aboriginal owners sometime since The Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act of 1976, which for the first time in Australia’s history recognised the relationship between aborigines and the land. The brown areas you see on the map, for example, represent such ownership of land – which lasts ‘forever’ and includes all mineral and oil rights under the first 150mm of soil. The white area marks a pastoral lease from the government to the Supplejack Downs cattle station – which means the station owners do not strictly ‘own’ the land, only lease it from the government on a 99 years renewable basis. The other catch is they have no rights to anything of value under the first 150mm of soil.

So, how does geography play a part in all this? The brown and white areas we see on a map of the North Territory tells us a lot about the surface ‘value’ of the land in terms of water and the capacity to support livestock (predominantly cattle in this case), and the hidden ‘value’ of the land in the form of mineral and oil deposits. They also give us some clues as to the whereabouts of landforms and geographical features in the landscape that are considered sacred by local aboriginal ‘guardians’. The reasons for both are as follows:

When the Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act was passed in 1976, the only land allowed to be claimed was land outside town boundaries and that not already owned or leased by anybody else. This, for the most part, meant either semi-desert or desert as any ‘valuable’ land with water on it (in the form of springs or bores) or vegetation that could support cattle on it, would already be spoken for. So, you could say that only land that was useless to the settlers would be given back, as a form of tokenism to defuse the rising pressure the government was facing from aboriginal groups seeking Land Reform from WW2 on. The brown areas therefore largely represent desert regions of little economic use, whereas the white areas represent pastoral leases on land that has water or is in some other way of economic value to the people farming it.

Sacred sites are also key to the whole Land Rights Issue, as one of the conditions for land to be given back to its traditional aboriginal owners under the Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act is that a claimant has to prove under aboriginal law that they are responsible for the sacred sites on the land being claimed. Such sacred sites represent evidence of a dreamtime ancestor having passed that way and left some mark: a pile of stones or even a tree. Some sites are very obvious – like Uluru (Ayers Rock). Others are less so and might not even be visible to the human eye. So the geography of the landscape is very often instrumental for determining whether a piece of land is returned to its traditional aboriginal owner or not.

We can conclude therefore that by looking at a Land Ownership map of North Territory we can make some rough guesses as why certain areas are coloured the way they are and what assets – either economic or religious – the land holds.

Suggested Learning activities: research an example of land ownership conflict in your local area and make some calculated guesses as to what ‘value’ the land represents to the interested parties and for what reasons they might therefore be in conflict with each other.